In my latest chapter in a book called “Meaningful Journeys” edited it by Alec Grant and Elizabeth Lloyd-Parkes, I write that, “I’m a spiritually inclined agnostic”.

For an academic, this is a little like coming out of the closet.

I was raised with secular critical thinking, religious art appreciation, and sent to Catholic elementary school. At St. Monica, the priest would arrive on his motorcycle and tells us bible stories that were both funny and kind. I loved his visits, and his stories, though when it came time for confirmation, I was given a choice.

My father had a PhD in biochemistry and was a math and chess genius. He played the piano and like my mother, had a huge library. He liked to study economics, history, bridge, psychology, and metaphysics. He would tell me about a book he’d read on middle eastern politics one week, about diabetic health the next, and he had a copy of Barbara Brennan’s energy healing kicking around too. Never a dull visit, having cappuccino, Gouda, and homemade chicken vegetable soup with Pap. He invited the Jehovah’s and the Mormons in and served them food too; and he was an eccentric nerd and like me: comfortably, happily, and cheerfully open but unconvertible.

My mother, raised Catholic, taught us that it’s important to dialogue and not follow anyone or anything blindly. It’s fine to have teachers, but having gurus is dubious. I agree with her – I like to say, “I am not a joiner”.

I take after both my parents, I suppose, like many of us do when it comes to our religious inclinations; or maybe some of us do, while others, especially those who have had religion foisted on them, healthily and predictably rebel. I’m not sure what the research says, but I imagine we all hope that we’ve made a free choice about it – though I have my doubts whether there is such a thing.

What I know is that my parents show(ed) reverence for life, but they never insist(ed) on how to be reverent about it. Thank god for that!

When my Pap died, one of my sisters had a dream that she asked him what had happened to him after death and he replied, “I fell apart into a thousand bits of light”. I can just imagine him saying it.

At Christmas when we would visit my grandparents in the Netherlands, we would go to midnight mass in the church that my grandparents helped restore after their retirement in the town of Thorn, Limburg. Their interest in buildings and history shone through and in their home, I remember the warmth of tea and hot chocolate served with pastry and the loud guffaw of Opa and the delightful chortle of Oma. Their Dutch buffet now graces my Edmonton home. On it, Oma always had a tea tray and a Persian rug. In many ways, I follow in her footsteps.

I married at age 26 and have two children from that first marriage to Keath, a skilled painter who would paint a Christ every Easter and had embraced the readings of many traditions while respecting his parents and Lutheran background. We also took our children to mass on Christmas Eve with their grandparents, who welcomed me “as is, where is” and never pushed a religious agenda. I like to believe our daughters’ visual talent and draw to art comes from their father and their Oma, and that their refusal to be pushed into a particular way of thinking was learned by example. That they question assumptions as our family is inclined to do.

Keath and I married in a chapel and divorced in a court, but each of those happenings was equally loving, as our close friends and family know. Both beginnings and endings can be spiritual experiences. We found this out in part by questioning assumptions about marriage.

At around age 40, I reunited with an earlier love and we spent a decade together before his death from cancer in 2018. Frans was raised a Catholic and became an atheist, like so many of his generation who went to university. No self-respecting sociologist was going to be a believer! You might say he too was a product of his time, though he greeted trees on his walks home and thanked his shoes when they had served him long enough to be thrown. He called himself an animist though when a critical comment was made about Catholicism, his defence was quick and sure; he had been an altar boy and sung in the choir, though he admitted that though he hadn’t been messed with by priests, he knew of others who had. He was critical of organized religion and knew his European history well; he could name the reasons, “waarom het allemaal niet deugt!”

My serendipitous experiences, some of them mind-blowing, didn’t make a dent in his consciousness; he wasn’t one for “mystical experiences”. As we happily pursued our academic work together, my spiritual side slowly bubbled on the backburner. I didn’t mind. I smile as I write this and remember his good sense and our years of devotion to research and theory.

Two years before Frans died, when we didn’t yet know he was ill, we went to Madrid and on the top floor of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, as we meandered through that first section – medieval art – and I neared the corner to go left, my body and breath were arrested by this painting of Christ by Italian painter, Bramantino – or “little Bramante” as he called himself after his artistic master. Our eyes met, this Christ and I, and I wept –

Yes, my mirror neurons;

Yes, the archetypal God of compassion;

Yes, the mere fact I am Christian by culture and was raised with these images and icons;

All of that combined must be the reason I was so stirred.

Last year, I visited Madrid again, this time with Tim, my partner of several years, and I showed him the painting and took many pictures of it close-up, so I could come home with my images and commission a painting.

In early June 2023, Keath and his love Judy came over to deliver the painting. Keath handed it to me by the door and my response was the same as that first moment. And as I write this with the painting beside me, and I look over at it again, I melt into soft and spontaneous tears. For the sweetness and pain of life; I have suffered; others suffer; we are flawed and damned, and beautiful.

Life is excellent and heartbreaking; I haven’t found exceptions.

As I write this, I realize this is my Christmas letter. I won’t report further on the kids’ successes (I do that all year, anyway) or how we’ve all been working too many hours or that it isn’t snowing enough (though, it clearly isn’t and I’m worried).

In academia, religion is rightly viewed with a critical eye. A lot has been destroyed by humans claiming that God has sanctioned their actions; we see it happening now, again. You would think by now we would know better; we don’t. On this tiny ball of sea, mountain, forest and plain hurtling a thousand miles per hour in the observable universe of trillions of planets, we are a miracle and very screwed up. It’s hard to make sense of it, though we try.

Academia is not wise to ignore or deny or belittle our spiritual wiring. We seek meaning and most of us are happiest in service and when we have cultivated compassion for our broken humanity. Some people find their way to this through a ‘belief system’ while others don’t need such structures at all, but still experience transcendent moments that don’t fit neatly into rational paradigms. We can go to cathedrals; we can notice clouds, birds, and moons; we can write poetry, paint, dance, sing; we can walk across continents; there are many sacred paths.

When I divorced all those years ago, with young children, there were several religious friends who judged me harshly. I also have a friend, a devoted Christian, who had only kind words for me and unconditional support. An atheist friend was just darn mad at me, for reasons she couldn’t fully name. Under the circumstances, judgement was human as was compassion; maybe the believers felt more justified in their reasons for judging, I don’t know. Ironically, Keath comforted me; he showed me more than a “little Bramante” and that has been the case for these past 27 years, half of those years, as divorced co-parents and friends.

When I think of Christmas, I don’t feel a need to go to mass or to decorate the house or to reflect on the archetypal story of a special child’s birth. I don’t even feel a need to give or receive gifts, though I send the kids a bit of money so they can treat themselves.

These past years, I’ve had my share of pain and heartache.

What has helped me most during the tough times is self-compassion and I appreciate the people in my life who hold me gently in their hearts – those who know my flaws and can look at me the way Bramantino’s Christ does. If I forget to treat myself well, I walk over to the painting, which hangs in the centre of my house, and meet with a “little Bramante” and share it around.

As I finish this piece of writing and await a friend’s visit, the winter sun has just done its pivot and shines right in and warms me.

Hey, this, to me is Christmas.

Wishing you all “a little Bramante” in 2024.

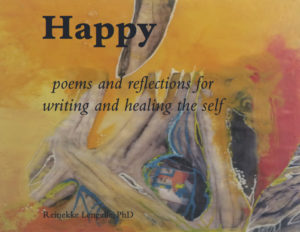

Painting, an interpretation of “The Risen Christ” by Bartolomeo Suardi, best known as Bramantino.